Ostrich Nutrition and Health

By: Fiona Benson, Blue Mountain International

Daryl Holle, Blue Mountain Feeds, Inc.

First presented at "Course specializing in the

Production of Ostrich Nutrition and pathology", UST (University of Santo

Tomas), Chile, April, 2001

Introduction:

Successful and cost effective production of Ostriches starts with the

Breeders. Most problems relating to fertility, hatching, chick

survivability, growth rates and deformities in the early weeks can be

connected to the Breeder rations with imbalanced or deficient

nutrients. Many of you will be hoping that I will be telling you

exactly which nutrient will fix particular problems that are being

experienced. The answer is that it is not that simple.

It has been our experience that most rations for Ostriches have been

extrapolated from other species with some significant miscalculations

in understanding the unique requirements of Ostrich. To provide a

‘single’ fix for a particular problem is not the answer as in most

cases the problems are as a result of a combination of severe

deficiencies and/or imbalances.

Daryl Holle has reported that of all species none demonstrate the

nutritional deficiencies as clearly as Ostrich and conversely none

respond to good nutrition so dramatically. Daryl Holle also reported

some years ago the improvements farmers were experiencing in the

performance of their breeders and quality of chicks on the ground. The

report referenced the following specifics:

If

these levels are compared to many rations on offer today it will be

found that the levels reported above are significantly higher. Breeding

birds need high levels of these vitamins at correct ratios to one

another to ensure a good nutrient transfer from hen to egg, and egg to

chick. Daryl Holle reported that the actual amounts consumed were much

more than indicated and that his research shows that feeding any less

than these amounts will cause chick survival problems to appear. The

severity of which is directly related to lessening amounts. Simply

increasing the levels of vitamins and minerals alone is not sufficient.

The other nutrient levels must match and be from a source that Ostrich

can utilise, as discussed in ‘The Basics of Nutrition’.

The amino acid profile must also be correct. The TRUE protein

determining factor is not whether a feed formula is 20% protein or 18%

protein, it is the amino acid profile of the formulas as amino acids

are the "building blocks" and foundation of protein. That is why on

occasion an 18% protein feed can work as well or better than a 20%

protein feed---because the amino acid profile is different between the

two formulas. Amino Acid profiles CHANGE or VARY according to the

feedstuff ingredients used in a formula and another reason why it is so

important to never substitute ingredients specified in a ration formula

with other ingredients that are not specified in the ration formula.

Daryl Holle has done considerable work on Amino Acid profiles in the

past years and discovered some most interesting facts. For proprietary

reasons it is only possible to share generalities that he knows to be

crucial to ostrich and a few tips on things that has proven not to work

well on ostrich.

It is Daryl Holle’s opinion that the most crucial amino acids for

ostrich are the levels of Lysine (essential amino acid), Methionine

(essential amino acid), Cystine (non-essential amino acid), and

Threonine (essential amino acid). It is also important to achieve an

adequate level of Arginine (non-essential amino acid) if at all

possible. Excellent productive performance can also be realized by

achieving a certain total level number of Methionine + Cystine when

added together, which is not uncommon for several other species but

ostrich is a very different total.

Level requirements of each of the above vary according to the age group

of birds being fed--also by the productivity goals desired from the

feed formula--especially in Breeder bird formulas and Slaughter bird

formulas.

Proven not to work well for amino acid profiles in ostrich is POULTRY

amino acid profiles. Not even close, but then neither are swine or

cattle profiles. Ostrich is rather unique but when understood, it is

most obvious as ostrich are not cattle, swine, or poultry!!

The Healthy Bird:

Much published data at this time demonstrates many of the ‘problems’

seen in Ostrich, but there is little published on the Characteristics

of a ‘healthy’ bird as these are seen all too rarely.

Figure 1: Hen in Prime Condition

For this reason I will provide some clear indicators on how to identify a healthy bird with comparisons where appropriate.

Figure 1 is a 3 year old hen at the beginning of the breeding season.

This is an example of a hen in PRIME condition. Note the excellent

feather condition and long tail feathers. Note how well rounded and

muscled she is. The good feather growth is indicative that she has all

the nutrients she requires, as this will be the last thing for her to

put reserves into. This hen laid in excess of 80 eggs in her first

laying season and commenced laying at the beginning of February in her

2nd Season (Northern Hemisphere).

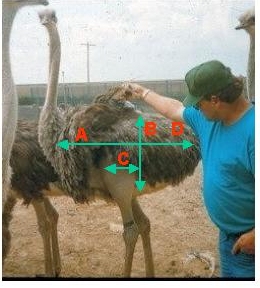

Figure 2: Prime Slaughter Bird

Figure 2 is an example of a Prime Yearling. Note the good length ‘A’, Depth ‘B’ and size of the Drum Muscle ‘C’. ‘D’ indicates the area of good muscling …the wider the bird the greater the area to develop good muscle. The farmer alongside the bird is 6ft 3in (1.9m), this provides an excellent indication of the size and depth of this bird.

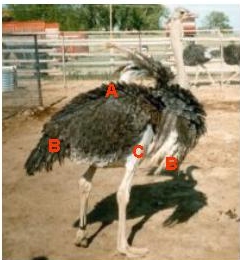

Figure 3: Fat Bird with No Meat

Figure 3, by comparison is a bird of a similar age and very typical of a Fat, No Meat Bird. ‘A’ indicates the fat across the back and it is important to be able to recognise the difference between ‘fat’ on a bird and ‘muscle’ on a bird. The poor feathering ‘B’ is one clue to the poor health status of this bird and ‘C’ - the minimal muscle on the Drum, where it is possible to see the leg bone through the drum is another clue that this bird is in poor condition.

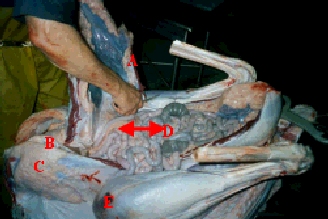

Figure 4: Healthy Carcass

FAT PAN:

Figure 4 is a slaughter bird on the cradle having the ‘fat pan’ ‘A’ removed. ‘B’ is indicating the location of the Heart and Liver situated below the Breast Plate and ‘C’ is indicating the minimal fat cover over the breastplate. ‘D’ is the Pancreas. This should be a Beige colour as in this picture. If it is brown, yellow or any other colour this is one clue to the inadequacy of the diet. The function of the pancreas is to produce digestive enzymes--if it is malfunctioning the digestive processes are decreased.

Figure 5: Perfect Fat Pan

The fat pan of the birds is a key indicator to bird health. Figure 5 is the fat pan after removal from the bird in Figure 4. It is near perfect…snowy white in colour and approx. 1 inch (25mm) to 1.5 inches (38mm) thick. The fat pan in this picture has been cut in half to demonstrate the thickness and evenness throughout. The fat pan is the ‘energy reserve’ for the Ostrich.

Figure 6: Fat Pan too thin and incorrect color

We

see many birds with NO fat pan or very thin as in Figure 6. Notice also

the colour in this picture. The fat can sometimes be even deeper

yellow. The yellow fat is an indication of an imbalanced and/or

nutrient deficient diet. The Fat Pan is required at times of stress,

high production, illness and severe weather. It provides the birds with

energy and nutrients quickly. The yellow fat is less easily mobilised.

The darker yellow the fat the greater the problem. We have seen birds

with excessive Dark Yellow fat die from starvation, as these birds were

unable to mobilise the fat fast enough when the additional energy was

required. A bird with a fat pan as in Figure 6 is unlikely to survive a

harsh winter and may not tolerate well a stress situation especially if

it encounters two stress situations following each other…even if fed a

proper diet.

This problem (or syndrome) is MOST COMMON in the industry today. When

adult and adolescent birds are dying for no obvious reason during times

of stress, the problem can usually be found in the fat pan with it

showing no reserves of fat left as in Figure 6.

This problem also shows up in Breeder birds on poor feeding programs.

Without the fat pan reserve that should be built up during the "off

season", breeder birds cannot be high production birds. Males will not

have the energy needed for high breeding activity; females cannot "call

up" the extra energy needed for high egg production. The fat pan

reserve amount is most crucial to productive breeding ostrich.

The "fat soluble" vitamins A, D, E, and K are also stored in the Fat

Pan reserve. These vitamins are most important to growth, fertility,

and chick survivability by yolk nutrient transfer from the hen. If

there is NO fat pan reserve, there also is NO vitamin reserve for the

bird to use when it needs it most--like during high egg production.

This syndrome occurs most commonly during the last half of the

egg-laying year on hens fed an improper diet causing the "tail end"

chicks to be stunted and very hard to raise.

Figure 7: Fat Pan, too thick

The

Fat Pan in Figure 7 shows a fat pan cut in half with a knife. The fat

colour is an excellent white, but the thickness is nearly 2 1/4 inches

(57 mm) thick. While this thickness is not a serious situation, it

indicates that the bird is slightly over fat, meaning the feeding

management probably needs some attention (bird was over-fed).

However, this condition is still far better than starving the bird to a

NO FAT condition. This thickness could also be an indication that the

feed formula is too high in protein or energy for this bird. In some

manner, the bird is getting slightly too much of something.

Since this fat pan came from a bird that was 12 months of age, it

indicates an over-fed condition and some dollars could have been saved

on feed costs. Otherwise, the fat pan is excellent and the meat from

this bird will be PRIME GRADE ostrich meat.

On Breeder birds, sometimes the fat pan can be as thick as 4 or 5

inches (10-13 centimetres). This much fat reserve in the fat pan would

classify this breeder bird as "obese". Obese breeder birds usually also

have extra fat in and around organs also causing production problems

and fertility difficulties in males. An overly fat breeder bird causes

poor breeding and egg laying--but they do need an adequate amount of

fat in the fat pan to be PRODUCTIVE.

Re-evaluating the feed formulas and the feeding management practices

and then implementing the changes can usually solve obese breeder bird

problems that cause “non-productive” birds. However, once the feed

formulas and feeding management is correct, it may take as long as two

years to get the breeder bird productive again.

Figure 8: Incorrect Fat Pan Color & Thickness

Figure

8 was taken off a non-producing Ostrich hen that was about 6 years of

age. The yellow fat and no reserves in the Fat pan is a clear

indication that she was severely deficient of nutrients and there was

absolutely no fat reserve for the bird to draw from to produce eggs--it

was starving and just trying to remain alive. It most likely would have

died in the coming winter months as this bird was from a very cold

climate in the wintertime.

It requires extra energy for the bird to survive through stressful

times. The "extra" energy source the bird uses frequently is the fat

pan. If the fat reserve in the fat pan is non-existent, the bird

immediately is faced with another stress during an already stressful

period--malnutrition.

“The liver filters the blood, metabolises foreign exogenous and endogenous substances, and synthesizes bile, many enzymes and proteins for bodily functions, as well as for the formation of the yolk. It also has a role in many metabolic processes such as carbohydrate utilization and storage." Source: Ratite Enclyclopedia

Figure 9: Unhealthy Livers from Slaughter Birds

The

above statement summary describes well the functions of the Liver and

its importance. The condition of the liver is another Key indicator to

the overall health of the Ostrich and adequacy of the rations.

We currently see livers demonstrating a number of different indicators of ration inadequacy.

Figure 10: Healthy Livers and Hearts

Figure

9 is a selection of livers at a slaughter plant and very typical of the

range of conditions that are currently experienced with many slaughter

birds throughout the industry. Figure 10 is an example of healthy

livers and hearts.

Clearly if a liver is not 100% healthy it is not able to perform its

tasks adequately. Poor nutrient transfer from Breeder to egg and chick.

Baby chicks will be discussed as a separate section.

HEART:

At this time we are also witnessing small hearts, hearts with

oedemas (jell like substance), very fat and odd colourations. These are

all signs of nutritional deficiencies of one degree or another.

| Figure 11: Healthy Heart | Figure 12: Heart Cross Section |

|

|

The

heart should have a little fat and that fat should be white in colour.

The hearts in Figure 9 have Oedemas …to touch the white coloured area

would feel jell like. The hearts in Figure 10 and Figure 11 are healthy

hearts. The line across the heart in Figure 11 is from sticking the

heartafter stunning to provide a better bleed out. |

|

REPRODUCTIVE ORGANS:

The

age birds commence breeding is influenced also by the quality of the

rations they are raised on from Day 1. Dr. Mike Jarvis has reported the

noticeable decrease in the size of the reproductive organs of many

current domesticated birds compared to those birds he dissected in the

wild. It can be expected that birds destined as future breeders will be

on no better a ration than most birds presented for slaughter and

therefore it can be expected that their livers are demonstrating

similar symptoms that are seen in the slaughter birds. This will affect

egg nutrient transfer.

It is also essential that birds are fed rations that maintain the

growth and development between the ages of 12mths and the commencement

of their first breeder season.

Figure 14: Egg Follicles of Productive Hen

Figure 14 shows the eggs from a cull breeder hen. She was culled at the end of the season and had laid well. The reason for culling was that she was a small hen. Note the hundreds of eggs from baseball size yolks to yolks the size of a grain of sand. This hen had been on a good nutritional diet for much of her breeding life, but not from Day 1.

Figure 15: Male Testicles, Small

Figure 15 has the Testicles and Fat Pan from a cull Breeder. The farmer reported this male as a poor breeder. The testicles are small and underdeveloped. The Fat Pan is thicker than one would expect from an active male towards the end of a long season. This male had been fed a good nutritional diet as a Breeder but not raised on a good diet.

Figure 16: Female Oviduct & Ovary

Figure 16 is a photo of the oviduct, Ovary and Vagina. Dr. Pier Bertoni, from Italy, has carried out research work on the reproductive organs with the use of ultra sound scanning. He has reported that the sizes of ovaries vary considerably. He has also referenced his observations of the birds drawing nutrients from the follicles when the rations are nutrient deficient. They do this to maintain their body nutrient requirements, which is a priority over egg production when their rations are nutrient deficient. Infections and certain problems with these organs are found more frequently with birds on a nutrient deficient diet. Problems with these organs can lead to egg laying difficulties and various problems with the egg shell.

CHICKS

When autopsying chicks at this time there are many different things

that one sees. The reason for this is the many, many ‘variables’ such

as:

These

few examples indicate that it is impossible to have clearly defined

answers for some time yet. The first step is to get the Breeder birds

onto the correct levels of Nutrition. It has been the experience of

Blue Mountain and others that once breeder birds are put onto the

correct levels of nutrients improvements in chick quality are seen

progressively over a two-year period. This is easy to understand when

one recognises how long the eggs are from first forming to resulting in

a mature egg laid. In some cases, if the Breeders have been severely

nutrient deficient in the past...and particularly during the

development stage of their lives, it is not possible to bring them back

to productive breeding. A severe shortage of Vitamin E and/or Vitamin

B1 over an extended period of time will result in sterility.

A strong and healthy chick at hatch should weigh around 1kg. Any chick

below 800grams is generally weak and in the future will most certainly

be deemed unviable and uneconomic. Even as late as the beginning of the

‘90s the old South African farmers believed that a healthy chick was a

yellow chick. They would choose yellow chicks over ‘blue’ chicks. A

yellow tinge can indicate nutritional malfunctions and metabolic

disorders taking place inside the body with jaundice type symptoms. It

is usually possible to identify a chick with a Bright yellow liver by

turning the chick upside down, parting the feathers, and viewing the

skin towards the front of the body. If the yellow liver is severe

enough, it can be witnessed through the skin as a yellowish color.

Blue, or Bluish tones on the rear of the chick indicate good metabolism

of heart, and other important organs. A chick may have a slight tan to

the liver when first hatched, but as the metabolism gets moving the

liver very quickly develops a normal coppery colour.

| Figure 17: Healthy 8 day old Chick | Figure 18: Severely Nutrient Deficient Chick |

|

|

Figure

17 is an example of a healthy chick. Note the copper coloured liver and

army green coloured yolk sac. The green colour is the bile required to

break down the fats in the yolk sac. |

|

Gastric

Stasis is when no digestive functions are taking place whatsoever…and

is currently seen all too often in young chicks. Bile production is the

key to breaking down the fats of the egg yolk. The chick needs these

yolk sac fats to sustain life in the early days of life…if that bile

production by the liver is non-existent or inadequate in the chick, the

chick will quickly become nutrient deficient and this can result in

Gastric Stasis.

Most are familiar with the deformities and conditions in Figures 19 to

22 and of course there are many other similar conditions seen. These

are all symptoms of severe nutritional deficiencies. Certainly there

can be a genetic influence…but most cases today are nutritional in

origin. Figure 23 is a 9 week old African Black chick and the size

chicks need to be if cost effective production of ostrich is to be

achieved.

| Figure 19: Leg Problems | Figure 20: Twisted Beak | Figure 21: Prolapsed Chick |

||

|

|

|

Figure 22: Poor Chicks

With the learning curve that has been witnessed over the past decade, there have been far too many chicks as seen in Figure 22. Many of these types of chicks have gone onto to be sold as Breeders.

Figure 23: Good Chick, 9 wks.

The

actual age of the chicks in Figure 22 is not known, but in my travels I

have visited some chicks that were this same size and condition at

9mths of age as the chicks in Figure 22. That is the severest case I

have personally witnessed of poor chick development.

Whilst it is possible to eliminate certain problems, such as leg

deformities through correcting certain nutrients…if the overall balance

of the rations is not corrected, it is clearly evident that cost

effective production will not be achievable.

SLAUGHTER BIRDS

The ultimate aim, of course, is to produce a quality slaughter

bird. This is where the success or failure of your nutritional program

can be seen. The belief that a slaughter birds should be 95kgs at

12-14mths has led to most producers believing that they were doing well

if they either achieve this target at 9mths or exceed it at 12mths.

Figure 24: Quality Carcass

Figure 24 is the carcass of a 12 month bird that produced in excess of 45kgs of saleable meat. Notice the width across the back and the significant muscle development. Note also the well developed and bulging Leg muscles. Meat from this type of bird will be excellent as the muscles were fast grown and demonstrate no muscle degeneration.

Figure 25: Poor Carcass

In

comparison Figure 25 is narrow across the back, the leg muscles are

demonstrating signs of muscle degeneration. Note how little back

muscling there is by comparison to Figure 24. This carcass is very

typical of most carcasses today. Why is this?

Many rations are low in Phosphorus, which is not only important in bone

growth, but also very necessary for muscle growth (meat production).

When phosphorus levels are low in the total diet, very little EXTRA

meat production is going to take place other than what the bird needs

to survive. The low phosphorus level also contributes to a poor

utilization of the high energy and again causes excess FAT production.

Calcium, Phosphorus, Zinc, Manganese, Copper, Selenium, Magnesium,

Potassium, and Salt are also important minerals/trace minerals that

assist with the total digestion process and are key to FAT production

and MEAT production. Vitamins A, D, and E also help with the

digestion/conversion process. In addition, the B-vitamins such as

Choline, Niacin, Biotin, etc, help convert body fat to mobilized energy

in the bird. If the bird has some body fat but cannot mobilize it for

use, it just gets fatter.

Minerals, Trace Minerals, and Vitamins must be BALANCED to the

rest of the ingredients in the diet so everything will work together.

Figure 26: Fillet Muscles after portioning

The carcass in Figure 24 will produce meat of the colour of Figure 26. Note the even colour throughout muscles that are typically demonstrating variations in colour. Note also that this meat has been exposed to the air for some time and demonstrating no signs of discolouration. Figure 27 is a typical example of this.

Figure 27: Multicolored Muscle

Multi-coloured

muscle meat can be caused by inadequate levels of Calcium, Phosphorus

and the major Vitamins A, and D. White to Pink coloured muscles are

sometimes referred to as "white muscle disease" in other livestock

species. However, it is actually a nutritional deficiency and not a

disease. Inadequate levels of Vitamin E and Selenium is the most usual

cause white muscle disease.

The correct levels of Vitamins A and E helps maintain the good red

colour and prevent the blackening of the meat on exposure to the air.

These vitamins act as antioxidants, which will keep the meat in the

package a bright red and extend the shelf life of the meat.

SUMMARY

From a nutritional point of view Daryl Holle will look at the

symptoms…be it leg deformities, poor egg quality, low fertility or

whatever…he then will identify the cause/deficiency of those symptoms

and the effect. From there he determines what is required to correct

that problem. It is then important to understand how the remedy affects

everything else to avoid new problems arising.

Copyright© of Blue Mountain all rights reserved