Blue Mountain

Commercial Ostrich Production

Economics

Fiona Benson, Daryl Holle

First Presented: World Ostrich Association Conference, Santiago, Chile March 2003

Introduction

In order for this industry to grow, birds must be produced, and all in the chain have to make a profit. One of the greatest limiting factors to development has been the belief that Ostrich slaughter weight is 95kgs at 14 months.

The reasoning behind the 14months is the belief that the follicles will not be mature any earlier. In 2001 and 2002, I slaughtered birds in South Africa that proved, beyond doubt, that skins from birds as young as 8 months can produce very acceptable skins. The results of this study are detailed in “Influences of Ostrich Skin Quality . . . Age or Nutrition?” [1] The impact on the economics of raising Ostrich, that birds can be slaughtered 4 – 6 months earlier are obviously very significant.

Agriculture has made many advances in technology over the past few decades in an effort to keep ahead of the Cost Price Squeeze. This paper will discuss how this applies to Ostrich production. Producers can either treat the birds as “Production Units” or as “Feed Cost Units”. What is the difference?

Production Units: When approaching production treating livestock as “Production Units” the ability to stay ahead of the cost price squeeze is achieved by reducing costs of the Units of production through increasing production. This requires increased input costs combined with high standards of management and genetic improvement programs. Producers will also be looking at the quality of the end products and consumer acceptability.

Feed Cost Units: The approach of these producers is to keep the input cost of the feed as low as possible with little concern for increased production or end product quality. Apart from end product quality, which deteriorates the more costs are reduced - the difficulty with this route is that there comes a point where it is not possible to reduce costs without compromising animal health and ability to reproduce successfully. Ostrich production is at this point on many farms throughout the industry.

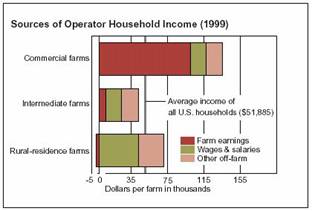

Over the past few decades agricultural technology has made tremendous advances and proof of the profitability of this new approach to agriculture is detailed in the USDA Farm Policy 2001. As can be seen from Figure 1, Commercial Farms contribute double the average US household income. The intermediate farms barely achieve any contribution to the household income, with Rural Resident Farms having a negative impact on their household income. These commercial farms are 8% of the total farms on 1/3rd of the land and produce 68% of the total US Agricultural output. The modern approach to agriculture is very successful and can be very profitable.

Figure 1 - Farmer Income [2]

Tables 1 and 2 list the current levels of production. The targets as laid out in “The New Ostrich Industry” columns are achievable as 5 year targets for producers treating Ostrich as “production units” and introduce correctly modern management systems. We would predict further that the feed conversion rates as set out under “The New Ostrich Industry” columns as 5 year targets can be halved again in 10 years. This results in extremely ‘cost effective production’ and truly taps the production potential of the Ostrich.

|

Table 1 - Comparison of Production Statistics |

||||

|

ITEM |

CURRENT |

NEW OSTRICH INDUSTRY |

||

Start Breeder Egg Laying |

3-4 years of age |

2 - 3 years of age |

||

Eggs Per Annum |

0-100+ Inconsistent year to year |

100+ Consistently |

||

Fertility |

10% - 95% |

>95% |

||

|

Hatchability |

>50% |

>90% |

||

|

Survival |

0 - 100% typically 50% |

>90% |

||

|

Liveweight at 12 months |

+/- 95 kgs |

>120 kgs |

||

|

Feed/Live Weight Conversion – 12 months of age |

12:1 |

<4:1 |

||

|

Feed/Liveweight Conversion - 7 months of age |

>4:1 |

<2.5:1 |

||

|

Carcass Weight - 12mths of age |

36 - 50 kgs |

>65 kgs |

||

|

Meat Yield - 7mths of age |

20 - 25 kgs |

>25 kgs |

||

|

Meat Yield – 9mths of age |

20 - 30 kgs |

>35 kgs |

||

|

Meat Yield – 12mths of age |

20 - 32 kgs |

>45 kgs |

||

|

Table 2 - Comparison of Carcass |

||||

|

TRAITS |

CURRENT PRODUCTION |

NEW OSTRICH INDUSTRY |

||

Fat - Type |

Yellow |

White |

||

|

Fat - Quantity |

Nil – 20% + Liveweight |

+/- 6% Liveweight |

||

|

Liver |

Many different colours - extreme variability |

Mid Red/Brown, even coloration |

||

|

Muscles |

Variable from Very Dark to Pale Pink and White. Blackening with Oxidation |

Even Red colour throughout, colour improving with Oxidation |

||

|

Meat Yield |

25 – 30kgs, 9-14mths of age |

40 - 55kgs, 9-14mths of age |

||

|

Organs |

Small |

Well formed and good growth |

||

|

Hides |

20% - 30% First Grade |

+70% First Grade |

||

How to achieve the levels of production as laid out in the New Ostrich industry columns and explanations as to the need of a long-term view to be taken, will be the subject of several presentations later in the conference. This discussion will focus on the effect on the economics of production and processing.

Economics of Production Agriculture

Production Goals with Ostrich are:

- Breeders: Number of Slaughter Birds/Breeder

- Slaughter Birds: Kilos Meat

- Slaughter Birds: Quality Skin

- New Breeders: Early Puberty

The cost of the feed is the largest input cost. Most everyone is aware that this has the greatest influence on basic health of the livestock, levels of production and quality of end products. In order to increase production, rations have to contain high levels of nutrients and use quality ingredients. This obviously comes at a higher cost than a ration designed to do little more than keep an animal alive. Production rations for Ostrich do come at considerably higher cost per tonne, but given the birds’ low daily intake and production potential, this can be an extremely good investment and is now proving to be an essential investment for profitable Ostrich production.

Breeders

Many believe that the number of eggs breeders lay and/or day-old chicks produced is the measure by which their breeder production success is gauged. Of course the goals are to achieve as many eggs as possible – but of far greater importance is the number of progeny that make it to slaughter.

|

Ration Performance |

Ration cost/ tonne |

Kilos per Trio/ annum |

Feed Cost per trio/ annum |

Slaughter Birds/Trio |

Breeder Kilos/ Chick |

Breeder Feed Cost per Chick |

|

|

High Performance 100% |

$350.00 |

2400 |

$840 |

120 |

20kgs |

$7 |

100% |

|

80 |

30kgs |

$10.50 |

150% |

||||

|

Medium Performance 75% |

$262.50 |

2400 |

$630 |

60 |

40kgs |

$10.50 |

150% |

|

Feed Cost Unit 50% |

$175.00 |

2400 |

$420 |

30 |

80kgs |

$14.00 |

200% |

|

2800 |

$490 |

30 |

93kgs |

$16.33 |

233% |

||

Table 3 – Breeder Performance

Table 3 proves the economic benefits of feeding breeders for production. It is doubtful that one could achieve a ration in any country for as little $175/tonne without loosing birds; however, the level of production is very typical of what is being achieved today and even at that low cost, the cost per Slaughter chick is very high.

When moving to performance feeding, it may take several years to achieve herd averages of 60 slaughter birds/hen – 40 should be achievable more quickly. What we do know is that without these nutrient levels, it is not possible to achieve such production levels.

Working with rations (medium performance) that are higher in nutrient levels than many we see today, but are still short on some nutrients, there is some improvement in performance. What is interesting is that as a result of reduced numbers of chicks, the cost per chick remains the same as the lower performance achieved on the production rations.

There are other commercial benefits associated with achieving the higher levels of production:

- With greater hatchability of the eggs, the incubation costs per chick are reduced

- With more chicks produced per breeder – fewer breeders are required for the same level of production

- Less infrastructure

- Less Capital Investment

- Less labour

- Reduced Chick Mortality

- Stronger Chicks convert feed more efficiently

- Identification of Superior Genetics leading to genetic improvement programs

As can be seen, breeder production can be extremely lucrative, but to achieve the higher levels of performance will also require high standards of management.

Slaughter Birds

Producer

As can be seen, cost effective production with slaughter birds starts with the breeders. This influences:

o Cost of Chick

o Chick Mortality

o Excellent Feed Conversion from hatch

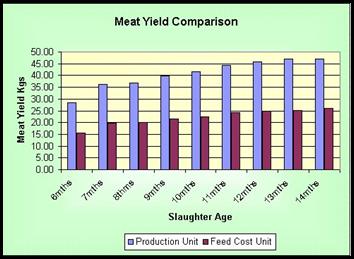

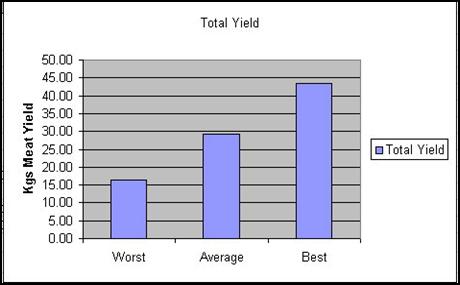

Figure 2 - Comparative Meat Yields

Figure 2 is an illustration of the difference in meat yields achievable when treating the birds as ‘Production Units’ and ‘Feed Cost’ Units. The article “Potential Meat Yield of Ostrich” discusses and proves the production potential of Ostrich. [3] This discussion will be limited to the economic benefits.

Clearly if meat yields can be nearly doubled, the difference in Revenue will be very significant, provided the processor pays the farmers correctly. This we will discuss later.

Production of a slaughter bird is measured by:

- Quality of Carcass at Slaughter

- Conversion of Feed to Live Weight and Boneless Meat

- Yield of Boneless Meat at Slaughter

- Yield of Primary, Secondary and Trim Muscles

- Age of Slaughter

- Percentage of Grade 1 Hides.

The Quality of the Carcass will determine the ability to achieve the best price for the meat at sale. Maximising the Ostrich’s ability to convert feed to growth and muscle is the secret to success.

There are various terms used as measures of performance:

Feed Conversion Rate (FCR): The rate at which feed consumed is compared to liveweight gain. For example - an FCR of 4:1 means that for every 4kgs. of feed consumed, 1 kg of live weight is achieved. All feed intake must be calculated – including any grazed material. See Table 1 for target FCR rates.

Liveweight: Weight of Live bird.

Yield Percentage: The weight of boneless/saleable meat expressed as a percentage of liveweight. For example - the yield percentage of a bird weighing 130kgs at slaughter that produces 45kgs of boneless meat will be 35%. This measure is more important than liveweight achieved.

Carcass Weight/Rail Weight/Dressed Weight: Dressout percentage is the Deboned Meat Weight of the bird expressed as a percentage of the Total Carcass Weight of the bird using the Standards of Deboned Meat Weight & Carcass Weight (see below). Any bruising on muscles will have been removed.

Leg Weight: The first stage of the deboning process is to remove all the muscles attached to each leg…the bone is still in. Some slaughter plants pay on Leg Weight.

Boneless Meat: All saleable meat taken from the carcass. (see below)

- Carcass Standard: All fat trimmed off the carcass as reasonably as possible, Neck no longer than 6 inches (15 cm) in length, leg bones sawed no longer than 6 inches (15 cm) below the hock, rib cage, wings and tail left on carcass, breast plate removed.

- Deboned Meat Weight Standard: Silver/Blue skin left on the meat, Major Tendon ends removed. Not included in the weight are Rib Cage meat, Neck meat, Organ meat or Fat.

Successful commercial livestock farmers watch these measurements very closely. With Ostrich responding so well to good nutrition and extreme sensitivity to accuracy in view of their low daily intake of feed – it takes very little improvement to make a significant impact on the profit line.

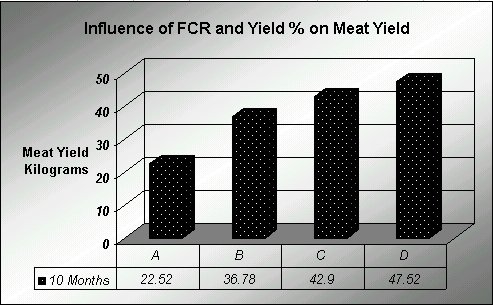

Figure 3 Influence of FCR and Meat Yield % on Meat Yield

Figure 3 assumes the same feed intake but different Feed Conversion Rates.

A: Current Average Performance

B: Assumes 3.6:1 FCR and 30% Yield Percentage

C: Assumes the same FCR as B but an improvement in Yield Percentage to 35%

D: Assumes an improvement in FCR to 3.25:1 and 35% Yield Percentage

To get a feel for how this is converted to revenue - Based on Current European Farmer Graded meat yield payment system, the bird revenue on Meat would be:

A: $ 84.22

B: $188.13

C: $228.87

D: $253.52

That represents a difference in revenue on Meat alone of $169.30 from worst to best.

European Feed Cost for B, C and D would be approx: $150.00 delivered to farm. Feed costs for A will be about 75% of that cost at around $110.00. Worthy of note is that a bird yielding 22kgs of meat will be marginal for skin size and also correct follicle development – therefore the skin value will be lower than the skins from B, C and D birds. Current Farmer value for reasonable skin is $50.00 with deductions for damage, poor follicle development or small size. This revenue is NOT included in these figures.

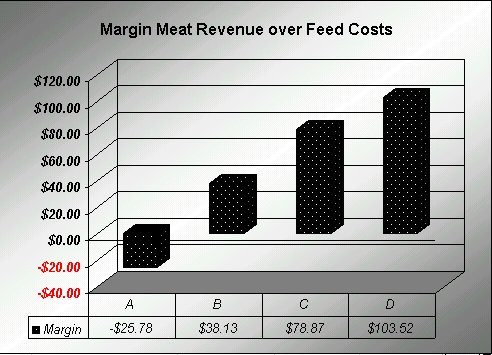

Figure 4 Margin Meat Revenue over Feed Costs

As can be seen from these examples, increased inputs – when combined with commercial standards of management – will significantly improve margins. These are the basic principals of Commercial Production Agriculture when treating the birds as ‘Production Units’.

The lack of understanding of these principles, combined with the immaturity of the industry and markets, producers have been forced to feed the bare minimum to survive. This has resulted in a downward spiral that has to be reversed. In view of the low level of the current breeder stock as a result of the management systems over the past, it will take time to reach consistent levels of production. The performance of B is very achievable now with reasonable genetics. The performance of C will be achievable now with the better genetics and can be expected for herd averages in 3-5 years for the farm implementing commercial production systems, with the top performing birds achieving the levels of D. The performance of D as herd averages will take another few seasons but is very achievable and possibly surpassable 10 years from now.

Processor

It is extremely important that producers and processors understand the economics of production both at farm level as well, as processor level and all in the chain have to be profitable. Processors have been faced with significant difficulties. These have been detailed in “Understanding Difficulties of Economic Processing of Ostrich” [4]. In this discussion we will just cover the basic principals.

Figure 5 - Processor Bird Yields

Processors are reporting significant variations in meat yields. Figure 5 represents the Worst, Average and Best meat yields of one processor over a period of 18 months. As can be seen it would take nearly 3 birds with the worst yields to provide the same meat as one of the best birds. The slaughter and processing costs per bird are very similar regardless of meat yield.

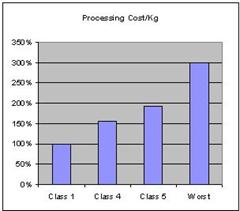

Figure 6 - Comparative Processor Costs

Figure 6 demonstrates the impact of those processing costs. The small birds costing 300% more per kilo of meat than the best birds to process. This is potential revenue lost to the producer of the lower weight birds.

Other difficulties that these variations create are:

- Planning Production

- Consistency in Size of Muscles

- Consistency in Supply as meat per slaughter batch varies

- Inconsistent Quality of Meat

- Disappointed Customers

With producers and processors working as a team, a more profitable bird for both the producer and the processor can be produced. This will also ensure progress toward high quality meat that is most desirable to our consumer/customers so they will come back for more.

Currency Fluctuations

One other influence on productivity comes from the approach to working with currencies subject to rapid changes in value. The danger comes from measuring costs in the local currency instead of a hard currency – most usually the US Dollar. Most countries working with soft currencies are net importers of the ingredients required for modern agricultural technology, including fertilisers, sprays, vitamins and minerals. The prices of the major/productive ingredients in livestock rations tend to follow International prices and can be subject to significant rises in local currency. This has certainly been the case here in Chile, and we experienced the same in South Africa.

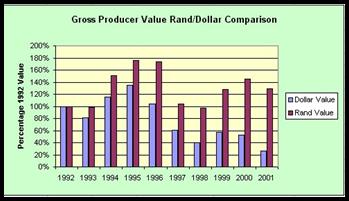

Using the South African Ostrich Industry as an illustration, you can see the dangers of measuring revenue and costs in local currency.

In a competitive product market, there is danger in only watching the correct return of local currency achieved instead of watching the Dollar value. The South African Farmer at the end of 2001 was achieving 130% of the Rand value for a bird in 1992. However, in view of the devaluation of the Rand, as can be seen in figure 7, it was only 20% of the US Dollar value.

Figure 7 - Influence of Currency Devaluation

At the end of 2002 the Rand has recovered significantly, and this has resulted in an estimated R300 reduction in the value of a bird. This will put the Rand value back at 1992 values and clearly does not cover inflationary growth over the period.

The South African industry and their researchers have pursued a policy of treating birds as “Feed Cost Units”. Therefore producers now find themselves with serious difficulties to recover from this situation with no improvement in meat yields to provide producers with increased revenue as a result of increased production. Researchers are reporting 45% - 60% chicks from Eggs laid, Chick mortalities remain unacceptably high and a 14mth slaughter age bird is still recommended - all as a direct result of the ‘feed cost unit’ policy. The situation is such that one major processor at the South African Conference in October 2002 issued the warning: “No Raw Material – No Industry”.

Conclusion

Raising a quality bird for the processor and customer requires a program

of “production” nutrition accompanied by good feed management based on

“production” standards, a farm management program that includes an adequate

recording system and then implementing a genetic improvement program. Treating

livestock as “Production Units” rather than “Feed Cost Units” is how a

“production” livestock industry succeeds and crosses over into the

“economically viable arena”. How this is achieved will be discussed during the

course of this conference.

[1] Benson and Holle Nutritional Bulletin No. 79

[2] Source USDA Farm Policy 2001

[3] Benson and Holle Nutritional Bulletin No. 81

[4] Benson and Holle Nutrional Bulletin No. 82

Nutritional Bulletins are available at: http://www.blue-mountain.net/bulletin/index.htm

HOME